|

|

|

Born

in 1924 in New York, Harvey Kurtzman grew up with comic books.

He was drawing a regular strip titled Ikey and Mikey in chalk

on the neighborhood streets before he was in his teens. He had

his first drawing published in 1939 in an issue of Tip Top

Comics. He was paid $1 for his contest-winning art. But it

wasn't until late 1942, at the tender age of 18. that he broke

into the big time - the commercial comic book market.

Born

in 1924 in New York, Harvey Kurtzman grew up with comic books.

He was drawing a regular strip titled Ikey and Mikey in chalk

on the neighborhood streets before he was in his teens. He had

his first drawing published in 1939 in an issue of Tip Top

Comics. He was paid $1 for his contest-winning art. But it

wasn't until late 1942, at the tender age of 18. that he broke

into the big time - the commercial comic book market.

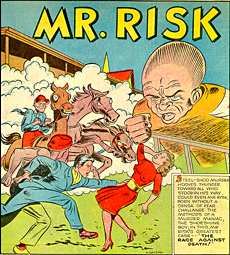

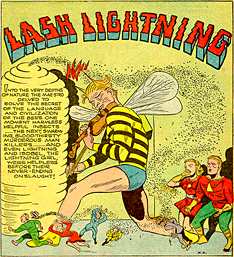

He got a job working for Lou Ferstadt, who produced comic features for publishers like Prize and Ace. Ferstadt hired young artists in or fresh out of school (with Kurtzman, that was the High School of Music and Art) to draw the features that filled out the monthly or bi-monthly titles of his clients. Hired first to assist Louis Zansky in the production of Classics Illustrated's Moby Dick adaptation, his job was to fill in the blacks to save the "real" artist's time. Interestingly enough, Kurtzman's first signed effort [just added, new information!] was the cover of Super-Mystery Comics volume 3, number 3, as well as the Mr. Risk story inside. Dated January of 1943, the work was done and actually published in 1942. The Lash Lightning strip is from another Ace title, Four Favorites #9 (February 1943). He did strips for Quality, Bill the Magnificent and Flatfoot Burns, but the war interrupted his career.

Aside: He says he went into the service at 18 - which means before October of 1943 and stayed for 2½ years which puts him getting out circa April 1946. His work continues to appear in comics during that time frame. Two unique efforts were installments of a Black Venus strip for Contact Comics - one in mid-1945 and one that appeared in early 1946. A sample of the earlier strip is below.

Right about now, a lot of you are asking yourselves "who is this Kurtzman guy and do I really want to read any more about him?" Let me just assure you that, despite the humble beginnings chronicled above, Harvey Kurtzman was the most influential and arguably the most important cartoonist of the 20th century. Bear with me a while and I'll prove it to you.

As the comic market changed again in the late 1940's, Kurtzman again found himself scurrying for work amongst the New York publishers. He tried to start his own commercial art studio with Charles Stern and Music and Art classmate Bill Elder. Elliott Caplin, an editor at Toby Press, hired him to produce some work for his company and for the first time the mature Harvey Kurtzman applied his talent to an extended narrative of his own devising. His attempt at Timely to work on some of the company's many teen/family comedy strips had been a failure for all concerned and left him convinced that future concepts and the scripts would have to be his own if he was going to succeed in comics.

If

the above splash panel from the Pot Shot Pete story

(from John Wayne Adventures #6) reminds you of Mad Magazine,

there's a very good reason for that. While making the rounds of

comic publishers in 1949, Harvey chanced upon the offices of EC

Comics. While showing his portfolio to the owner, Bill Gaines,

he was both pleased and surprised that Gaines laughed out loud

at his humor, which most other editors found puzzling or sophomoric.

Gaines hired him. At first Kurtzman did stories and covers for

the science fiction and horror titles, but it wasn't long before

he was editing titles that he soon made very much his own. Two-Fisted

Tales and Frontline Combat were some of the finest

war (or, more precisely, anti-war) comics ever published. Kurtzman

had some of the greatest comic artists available to illustrate

the stories that he wrote, but he still felt compelled to show

them how he wanted each script rendered. Look at the thumbnail

"breakdowns" at right that he provided for John Severin

and check out Severin's interpretation of the bottom tier panels

below.

If

the above splash panel from the Pot Shot Pete story

(from John Wayne Adventures #6) reminds you of Mad Magazine,

there's a very good reason for that. While making the rounds of

comic publishers in 1949, Harvey chanced upon the offices of EC

Comics. While showing his portfolio to the owner, Bill Gaines,

he was both pleased and surprised that Gaines laughed out loud

at his humor, which most other editors found puzzling or sophomoric.

Gaines hired him. At first Kurtzman did stories and covers for

the science fiction and horror titles, but it wasn't long before

he was editing titles that he soon made very much his own. Two-Fisted

Tales and Frontline Combat were some of the finest

war (or, more precisely, anti-war) comics ever published. Kurtzman

had some of the greatest comic artists available to illustrate

the stories that he wrote, but he still felt compelled to show

them how he wanted each script rendered. Look at the thumbnail

"breakdowns" at right that he provided for John Severin

and check out Severin's interpretation of the bottom tier panels

below.

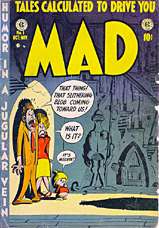

Kurtzman

discovered within himself a degree of perfectionism that gave

his stories more impact and verisimilitude. It also slowed up

his output and one way to earn more money was to go back to the

humorous material that had appealed to Gaines at that first meeting.

In October of 1952 Mad #1 hit the stands. Edited and inspired

by Kurtzman, the comic book was very much the reflection to his

sensibilities and sensahumor. It took about a year to find its

audience. It was, after all, a comic book, but the humor was aimed

at adults. For 23 issues of the comic book and five issues as

a magazine, Kurtzman guided the style and direction of Mad.

With issue 29 (Sept. 1956), Kurtzman was gone. Though Mad

had been his baby from conception, Gaines was banking on the title

to be the life raft of his sinking EC Comics line. As a

magazine, it wasn't perceived as being a comic and especially

not an EC comic. Kurtzman literally forced the change of editorship

when he insisted on a controlling interest in the magazine. I

think he knew Gaines wouldn't and couldn't give in. I don't think

Kurtzman cared.

Kurtzman

discovered within himself a degree of perfectionism that gave

his stories more impact and verisimilitude. It also slowed up

his output and one way to earn more money was to go back to the

humorous material that had appealed to Gaines at that first meeting.

In October of 1952 Mad #1 hit the stands. Edited and inspired

by Kurtzman, the comic book was very much the reflection to his

sensibilities and sensahumor. It took about a year to find its

audience. It was, after all, a comic book, but the humor was aimed

at adults. For 23 issues of the comic book and five issues as

a magazine, Kurtzman guided the style and direction of Mad.

With issue 29 (Sept. 1956), Kurtzman was gone. Though Mad

had been his baby from conception, Gaines was banking on the title

to be the life raft of his sinking EC Comics line. As a

magazine, it wasn't perceived as being a comic and especially

not an EC comic. Kurtzman literally forced the change of editorship

when he insisted on a controlling interest in the magazine. I

think he knew Gaines wouldn't and couldn't give in. I don't think

Kurtzman cared.

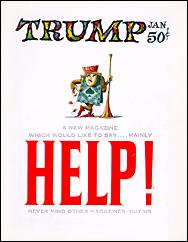

Based

on the timing of his next effort, I think he had a plan already

in place to go Mad one better. Joining with Hugh Hefner

of the burgeoning Playboy publishing empire, in January of 1957,

he produced the first issue of Trump. Quite literally a

trump card, it was the best of the Mad sensibilities and

the best of the Mad artists (Will Elder, Wally Wood, Jack Davis) presented in a slick

magazine format that even boasted a foldout, just like Playboy.

Based

on the timing of his next effort, I think he had a plan already

in place to go Mad one better. Joining with Hugh Hefner

of the burgeoning Playboy publishing empire, in January of 1957,

he produced the first issue of Trump. Quite literally a

trump card, it was the best of the Mad sensibilities and

the best of the Mad artists (Will Elder, Wally Wood, Jack Davis) presented in a slick

magazine format that even boasted a foldout, just like Playboy.

What it didn't have, apparently, was a commitment from Hefner.

It lasted for all of two glorious issues. At which point all of

the artists who had hung their star to Harvey's wagon, said a

collective "screw it" and pooled their money to finance

the publication of their own magazine. Aptly named Humbug,

it debuted in August 1957. It was comic book size but black and

white and too heavily text-laden to appeal to the average comic

book reader. Despite an 11th hour shift to magazine format with

issue ten, it only lasted 11 issues.

At

which point in his career, Harvey seems to have thrown up his

hands, rolled up his sleeves, reached for his destiny one more

time and started over with the, also aptly named, Help!.

Published by Jim Warren, Help! relied a lot on photography.

Old movie stills were fitted out with hip new captions and complex

and crazy scenarios were depicted with photographs in a comic-book-like format called "fumetti" by the Italians.

At

which point in his career, Harvey seems to have thrown up his

hands, rolled up his sleeves, reached for his destiny one more

time and started over with the, also aptly named, Help!.

Published by Jim Warren, Help! relied a lot on photography.

Old movie stills were fitted out with hip new captions and complex

and crazy scenarios were depicted with photographs in a comic-book-like format called "fumetti" by the Italians.

It's at this juncture that Kurtzman's influence on the humor/satire scene begins to show. With a small budget, he was able to attract an impressive array of stars and future stars to his magazine. The cover to issue one (at right) features Sid Ceasar, a major TV comedy star of the day. Inside was a short story by Rod Serling whose Twilight Zone was the current TV success story. The covers to the next ten issues read like a Who's Who of contemporary comedy: Ernie Kovacs, Jerry Lewis, Mort Sahl, Dave Garroway, Jonathan Winters, Tom Poston, Hugh Downs, and Jackie Gleason. Using impressive cover stars and a mixture of his own work, that of Will Elder, and old public domain photographs and movie stills, and the aforementioned fumettis, Kurtzman was able to gradually build a magazine to rival the longevity of his original success with Mad.

For five years, from Aug. 1960 to Sept. 1965, and 26 issues, Harvey received fumetti help with appearances from writers and comedians Dick Van Dyke, Gloria Steinem, Roger Price, Sylvia Miles, Orson Bean, Algis Burdrys, Ed Fisher, Phil Ford, Mimi Hines, Henny Youngman, Jack Carter, Jean Shepherd, Bernard Shir-Cliff, Russ Heath, Woody Allen, John Cleese, and many others.

Artists and writers who helped out were pretty famous, too: Gahan Wilson, Ed Fisher, Paul Coker, Jr., Phil Interlandi, Arnold Roth, Arthur C. Clarke, Ray Bradbury, Jack Davis, John Severin, Al Jaffee, and HK and WE produced their infamous Goodman Beaver parodies here, too.

The death of Help! in 1965 led almost directly into the underground comix movement. Kurtzman was the inspiration for many of the seminal cartoonists of the underground who had grown up after exposure to Mad. They followed his work in Trump, Humbug and many contributed to the "Public Gallery" in Help!. Kurtzman paid the munificent sum of $5 for each piece he used. Among the future radical stars whose first nationally published work appeared there include: Skip Williamson, Dennis Ellefson, Don Edwing, Stew Schwartzberg, Gilbert Shelton (including Wonder Warthog in 1963!), Terry Gilliam, Jay Lynch, Jim Jones, Hank Hinton, Robert Crumb, Joel Beck, and others.

Half

way through the Help! run, Harvey got distracted by money.

As we might guess from his less-than-stellar ability to hold a

job for more than three years in a row, the promise of a steady

income must have been impossible to ignore. Once again it was

Hugh Hefner who held out the carrot. This time is was a color

strip in the pages of Playboy. Titled Little Annie

Fanny, it was to be a parody of all things sexy and hip.

With Elder's help, the two to seven page strips began to appear

in 1962 and continued erratically until 1988. Throughout his career,

Kurtzman had elicited a strong rapport with the artists who worked

with him. Little Annie Fanny was no different. The

painted format was very time consuming and required more effort

than Harvey and Will alone could manage. The assistants who pitched

in over the years are legion and legends: Jack Davis, Frank Frazetta, Russ Heath, Al Jaffee, Arnold

Roth, Paul Coker, Jr., Larry Siegel, William Stout and many others.

Half

way through the Help! run, Harvey got distracted by money.

As we might guess from his less-than-stellar ability to hold a

job for more than three years in a row, the promise of a steady

income must have been impossible to ignore. Once again it was

Hugh Hefner who held out the carrot. This time is was a color

strip in the pages of Playboy. Titled Little Annie

Fanny, it was to be a parody of all things sexy and hip.

With Elder's help, the two to seven page strips began to appear

in 1962 and continued erratically until 1988. Throughout his career,

Kurtzman had elicited a strong rapport with the artists who worked

with him. Little Annie Fanny was no different. The

painted format was very time consuming and required more effort

than Harvey and Will alone could manage. The assistants who pitched

in over the years are legion and legends: Jack Davis, Frank Frazetta, Russ Heath, Al Jaffee, Arnold

Roth, Paul Coker, Jr., Larry Siegel, William Stout and many others.

Blonde, blue-eyed, buxom and beautiful, Annie would get involved in the fad of the minute which Harvey would satirize. Will and friends would paint it and Hugh would print it in gorgeous color in the back pages of Playboy. The formulaic aspects of it must have grated over the prolonged life of the feature, but a steady paycheck is a seductive lure. There were reprint collections in 1966 and 1972.

Kurtzman was a great believer both in paperbacks and in reprints. While at Mad, he recycled some of his best Pot Shot Pete strips. In 1957, Ballantine Books published The Humbug Digest consisting of memorable material from Humbug. Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book was a 1959 original collection of strips. Executive's Comic Book in 1962 collected the Kurtzman/Elder Goodman Beaver strips from Help! - stories that are said to have inspired Hefner to hire them for Little Annie Fanny. Help!, itself, saw two collections, Help! and Second Help!-ing in 1961 and 1962. In 1985 he created Nuts!, a paperback humor magazine for teens that only lasted two issues. And 1988 saw the digest-sized autobiography, My Life As A Cartoonist.

Kurtzman kept occupied with other projects. Often considered the father of the underground comix, he contributed to several in the 1970s (Denis Kitchen's Snarf, the anthology title Arcade and others), had his own title, Kurtzman Comix in 1976, and was often found in the infrequent letter columns offering encouragement and advice. The Illustrated Harvey Kurtzman Index was published in 1975 with a new cover by Harvey. He received the Ink Pot award for lifetime achievement at the 1977 San Diego Comics Convention. In 1991 his From Aargh! to Zap, Harvey Kurtzman's Visual History of the Comics was published and a compilation of his Hey Look! and other early work appeared in 1992 from Kitchen Sink.

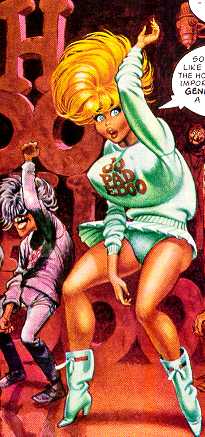

New graphic material in b&w showed up in 1986. It was done with Sarah Downs. I first encountered

it in the French publication L'Echo des Savanes. The strips

are vivacious and wordless and appear very spontaneous (see one

panel at left). Later, other collaborations with Downs appeared

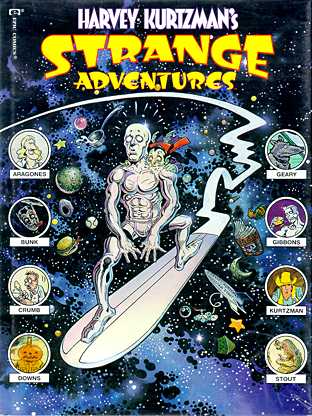

in Playboy. But the most revealing work appeared in Harvey

Kurtzman's Strange Adventures in which some of the greatest

modern comic book artists create new strips working from Harvey's

layouts, which are reproduced at the back of the book from his

pencils. Sergio Aragones, William Stout, Rick Geary, Sarah Downs

and Dave Gibbons demonstrate why Kurtzman was a master

of humor and pacing. Harvey manages a full strip solo and Robert

Crumb contributes a two page tribute explaining just how important

Kurtzman's work was to him in his childhood.

New graphic material in b&w showed up in 1986. It was done with Sarah Downs. I first encountered

it in the French publication L'Echo des Savanes. The strips

are vivacious and wordless and appear very spontaneous (see one

panel at left). Later, other collaborations with Downs appeared

in Playboy. But the most revealing work appeared in Harvey

Kurtzman's Strange Adventures in which some of the greatest

modern comic book artists create new strips working from Harvey's

layouts, which are reproduced at the back of the book from his

pencils. Sergio Aragones, William Stout, Rick Geary, Sarah Downs

and Dave Gibbons demonstrate why Kurtzman was a master

of humor and pacing. Harvey manages a full strip solo and Robert

Crumb contributes a two page tribute explaining just how important

Kurtzman's work was to him in his childhood.

There was even an attempt to revive the Two-Fisted Tales comic title in 1992. It lasted just two issues, despite the writing and layouts of Kurtzman. He died in 1993. As one of the true geniuses in comics, his legacy will always be with us. In the minds and hearts and strips of innumerable artists who grew up with his work, the influence will live on. And with the reprinting of the early Mads by Russ Cochran, there will always be the means for another generation to learn from the master.

To learn more about Harvey Kurtzman, see:

To learn more about Harvey Kurtzman, see:| Squa Tront | Jerry Weist and John Benson 1970 to 1983 |

| The Who's Who of American Comic Books | Jerry Bails and Hames Ware 1974 |

| The Illustrated Harvey Kurtzman Index | Glen Bray, 1976 |

| My Life As A Cartoonist | Harvey Kurtzman, Pocket Books 1988 |

| From Aargh! to Zap! | Harvey Kurtzman, Arts, 1991 |

| Hey Look! | John Benson Introduction, Kitchen Sink 1992 |

| Harvey Kurtzman: Retrospective of a MAD Genius | Cartoon Art Museum 1995 |

| The Vadeboncoeur Collection of Knowledge | Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr. 2001 |

|

Illustrations are copyright by their respective owners. This page written, designed & © 2001 by Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr. Updated 2011. |