Ronald

Searle was born March 3, 1920 in Cambridge, England into a working

class family. He wanted to be an artist and drew credibly by the

age of five and professionally at 15. At that age he was making

money for Art School classes by working at a parcel packing firm,

when the cartoonist for the Cambridge Daily News quit the

paper. In a move that was to affect a great deal of his life,

Searle decided to apply for the job. He got it and began a series

of 195 weekly cartoons, each of which paid more than a week's

salary at the packing house. Continued art classes were assured,

but several detours lay ahead.

Ronald

Searle was born March 3, 1920 in Cambridge, England into a working

class family. He wanted to be an artist and drew credibly by the

age of five and professionally at 15. At that age he was making

money for Art School classes by working at a parcel packing firm,

when the cartoonist for the Cambridge Daily News quit the

paper. In a move that was to affect a great deal of his life,

Searle decided to apply for the job. He got it and began a series

of 195 weekly cartoons, each of which paid more than a week's

salary at the packing house. Continued art classes were assured,

but several detours lay ahead.

In 1939 he received his Minister of Education Drawing Diploma and enlisted in the Territorial Army as an Architectural Draughtsman. He continued to submit drawings and cartoons to newspapers and magazines for the next two years, including the prototype St Trinian's panel which appeared in Lilliput in October 1941. That month, he shipped out to Singapore and hell.

One

month after he arrived, Singapore was surrendered to the Japanese

and Searle spent the rest of the war as a prisoner. The prison

camp at Changi and the forced labor details building the railway

from Ban Pong to Burma were horrendous realities. Searle was victim

and observer and recorder of atrocities and diseases and deaths.

He never stopped drawing, despite beatings, bouts of malaria and

beri beri, and a Japanese guard's pick axe in the back. His art

sustained him and, without doubt, many of his companions in misery.

A 1943 self-portrait is at left.

One

month after he arrived, Singapore was surrendered to the Japanese

and Searle spent the rest of the war as a prisoner. The prison

camp at Changi and the forced labor details building the railway

from Ban Pong to Burma were horrendous realities. Searle was victim

and observer and recorder of atrocities and diseases and deaths.

He never stopped drawing, despite beatings, bouts of malaria and

beri beri, and a Japanese guard's pick axe in the back. His art

sustained him and, without doubt, many of his companions in misery.

A 1943 self-portrait is at left.

Russell Davies, in his 1990 book, Ronald Searle, A Biography, has much detail about this portion of his life. Two vivid passages struck me especially hard:

"The Siam-Burma railway was completed on 25 October. A celebrated feature film, The Bridge on the River Kwai, later gave it to be understood that British personnel might have drawn some mad sense of achievement from their forced collaboration on this project. ...there was no question of wasting moral energy on the formation of an attitude to the railway. A man's own survival became his full-time task. Whatever fragments of concern were left over, he might donate to his fellows and the goal of getting as many out of the jungle alive as could make it."

and a quote from Russell Bradon regarding Searle, "If you can imagine something that weighs six stone (84 pounds) or so, is on the point of death and has no qualities of the human condition that aren't revolting, calmly lying there with a pencil and a scrap of paper, drawing, you have some idea of the difference of temperament that this man had from the ordinary human being."

His return to Cambridge in October of 1945 was followed by an exhibition of his war drawings and, in 1946, by marriage to the editor of Lilliput and the publication of Forty Drawings, a book of his art. England wasn't ready for the power of Searle's images and the book was a commercial failure. Another 1946 book, Le Nouveau Ballet Anglais, was published in France, also to no great financial success. His second life detour pointed to cartooning, and he embraced it.

He

made several forays into book illustration, but the cartoons were

paying the bills. 1948 saw publication of Hurrah for St Trinian's,

his first collection of cartoons and the first nail in the constricting

coffin of public preconception. Hurrah and The Female

Approach, in 1949, both featured cartoons on other subjects,

but it is for the images of the unholy girls' school that they

are most remembered. For five years he was to be saddled with

the chore of creating mischief for the girls to get up to until,

in his own 1953 Souls in Torment, he blew up the school

with an atomic bomb. If only that had been sufficient! At right,

they appear alarmingly healthy in The Terror of St Trinian's

from 1956. They went on to inspire a string of films that probably

grew increasingly embarrassing.

He

made several forays into book illustration, but the cartoons were

paying the bills. 1948 saw publication of Hurrah for St Trinian's,

his first collection of cartoons and the first nail in the constricting

coffin of public preconception. Hurrah and The Female

Approach, in 1949, both featured cartoons on other subjects,

but it is for the images of the unholy girls' school that they

are most remembered. For five years he was to be saddled with

the chore of creating mischief for the girls to get up to until,

in his own 1953 Souls in Torment, he blew up the school

with an atomic bomb. If only that had been sufficient! At right,

they appear alarmingly healthy in The Terror of St Trinian's

from 1956. They went on to inspire a string of films that probably

grew increasingly embarrassing.

By

1950 he was entrenched as the illustrator for Punch's theater

column, had been featured in an issue of The Studio, and

been sent to Paris with his wife, Kaye Webb, for a working holiday

that resulted in A Paris Sketchbook. For decades, Searle's

life would revolve around various trips for various magazines

that reveled in and were enriched by his illustrations made on

the spot. As Russell Davies points out, "He was not making

the world look funny, but experiencing it as funny; it was less

a style than a psychological condition."

By

1950 he was entrenched as the illustrator for Punch's theater

column, had been featured in an issue of The Studio, and

been sent to Paris with his wife, Kaye Webb, for a working holiday

that resulted in A Paris Sketchbook. For decades, Searle's

life would revolve around various trips for various magazines

that reveled in and were enriched by his illustrations made on

the spot. As Russell Davies points out, "He was not making

the world look funny, but experiencing it as funny; it was less

a style than a psychological condition."

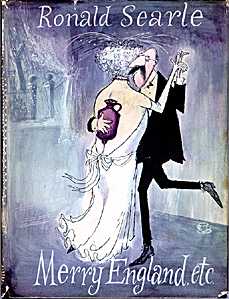

In

a most remarkably short time, Searle had become one of the foremost

illustrators in England. His own publishing company, Perpetua

Books (colophon above left), was started to collect his cartoons

into book form. Merry England, etc. and The Rake's Progress

were among the first published. In 1956, scarcely ten years after

starting his post-war career, he became a member of Mr. Punch's

Table and one of their highest-paid staffers. He stayed for five

years and, though officially working exclusively for Punch, his

contract allowed for work outside the country and offers began

pouring in from America. Among the first was an animated film,

Energetically Yours, for Standard Oil. Its edgy, energetic

style was to influence a generation of films, starting with One

Hundred and One Dalmations. His first visit to the U.S.also

led to a Punch feature, written by Alex Atkinson, By

Rocking Chair Across America,

the first of many such collaborations. It was an immediate success.

In

a most remarkably short time, Searle had become one of the foremost

illustrators in England. His own publishing company, Perpetua

Books (colophon above left), was started to collect his cartoons

into book form. Merry England, etc. and The Rake's Progress

were among the first published. In 1956, scarcely ten years after

starting his post-war career, he became a member of Mr. Punch's

Table and one of their highest-paid staffers. He stayed for five

years and, though officially working exclusively for Punch, his

contract allowed for work outside the country and offers began

pouring in from America. Among the first was an animated film,

Energetically Yours, for Standard Oil. Its edgy, energetic

style was to influence a generation of films, starting with One

Hundred and One Dalmations. His first visit to the U.S.also

led to a Punch feature, written by Alex Atkinson, By

Rocking Chair Across America,

the first of many such collaborations. It was an immediate success.

Davies again, "Where exaggeration was required, it took an organic form; Searle would take a style or taste and show it in the grip of some fantastic growth-hormone. Anybody could have had the idea of making a Texan automobile a riot of carbuncular rococo excrescences, but only Searle ... could have make the thing look as if it had arrived at that state by some sort of ghastly evolutionary process."

Holiday magazine became a regular outlet, often pre-empting time he might have spent for Punch. He became the first non-American illustrator to receive the National Cartoonists Society's Reuben Award in 1960. Life magazine sent him on assignment to Jerusalem for Adolf Eichmann's trial. His popularity grew and his life became less and less his own. Finally in 1961, he abandoned the detour and simply packed his bags, left a note for his wife and twins and departed for Paris to begin again down the road to Art.

This

journey began with a series of paintings that have yet to see

print. Previewed in an American gallery as "Anatomies

and Decapitations," these violent and disturbing paintings

(73 eventually) seem to have been an exploration and a release

combined. Searle wasn't sure where he was going, but the direction

seems to have been away from the biting, but approachable, satire

for which he was famous. The future, when it came, was going to

have a sharper edge.

This

journey began with a series of paintings that have yet to see

print. Previewed in an American gallery as "Anatomies

and Decapitations," these violent and disturbing paintings

(73 eventually) seem to have been an exploration and a release

combined. Searle wasn't sure where he was going, but the direction

seems to have been away from the biting, but approachable, satire

for which he was famous. The future, when it came, was going to

have a sharper edge.

Initially, though, that future looked much like the past, except there were fewer British assignments and a different traveling companion. His flight to Paris was as much towards the woman, Monica Searle, who remains his wife, as it was away from intrusions and obligations over which he had no control. And the line of drawings was changing - the pen nib was spreading and splotching in new, angular ways and the satire had a harder and more bitter bite. (see example from The Square Egg - above right)

Lighter

assignments did continue during the Sixties. He did the design

for the animated opening sequences for the films, Those Magnificent

Men in Their Flying Machines and Monte Carlo or Bust,

covers for TV Guide, travel illustrations for Holiday,

art for The New Yorker, a divorce from Kaye in 1966 and

marriage to Monica in 1967. Several exhibitions of his work were

staged and the public was exposed to the illustrations that made

other artists say, "Beware of Ronald Searle, the man is dangerous."

Why anyone would willingly put themselves in the jeopardy of his

pen is a mystery, but The Hudson Bay Company commissioned him

to document the annals of their 300-year old company. The Great

Fur Opera (1970) was the result and images like "Life

at the Bay" (at left) were pointed reminders of just how

dangerous a man Ronald Searle was.

Lighter

assignments did continue during the Sixties. He did the design

for the animated opening sequences for the films, Those Magnificent

Men in Their Flying Machines and Monte Carlo or Bust,

covers for TV Guide, travel illustrations for Holiday,

art for The New Yorker, a divorce from Kaye in 1966 and

marriage to Monica in 1967. Several exhibitions of his work were

staged and the public was exposed to the illustrations that made

other artists say, "Beware of Ronald Searle, the man is dangerous."

Why anyone would willingly put themselves in the jeopardy of his

pen is a mystery, but The Hudson Bay Company commissioned him

to document the annals of their 300-year old company. The Great

Fur Opera (1970) was the result and images like "Life

at the Bay" (at left) were pointed reminders of just how

dangerous a man Ronald Searle was.

The late 60s also brought forth Hello - Where Did All the People Go? (1968), Take One Toad (1968), The Square Egg (1968), Homage a Toulouse-Lautrec (1969), The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1969), and Secret Sketchbook (1970). His output was prodigious and becoming more "dangerous" with each drawing. His ability to observe and render the emotions (and images that could trigger them) was at an all-time high. His road to Art was widening and all facets of his artistic temperament were being nurtured. It was time, unfortunately, for another detour.

Monica was diagnosed with terminal breast cancer and it was only through the intervention (and invention) of chemotherapy that she survived. Leon Schwarzenberg took personal charge of her treatment and literally experimented her cure. Searle survived the ordeal, too, much as he had survived Changi - he drew. His life revolved around Monica and her treatments, but the need to create to fill up the anxious days was always there. In 1973 he became the first non-French living artist to exhibit at the Bibliotheque Nationale - a great honor marred only by the theft of three of his paintings. In September of 1975, the Searles decamped from Paris to a new, still more private life, in Haute-Provence.

There, in a small

French village, they had built a house during Monica's illness

- thumbing there noses at the disease. She still was recovering

when they arrived but has since been pronounced cured. Searle

celebrated by taking on more work. Since the move he has designed

commemorative medals for the French Mint (see left), allowed his

Paris drawings to appear in a "collaboration" with Irwin

Shaw, Paris! Paris!, produced lithographs of his drawings

(ah, Art!), created ads for American Express (ah, Commerce!),

published his cat books (ah, Sustenance), and created two of my

very favorites, The Illustrated Winespeak (at right) and

Slightly Foxed - But Still Desirable (ah, Satire!).

There, in a small

French village, they had built a house during Monica's illness

- thumbing there noses at the disease. She still was recovering

when they arrived but has since been pronounced cured. Searle

celebrated by taking on more work. Since the move he has designed

commemorative medals for the French Mint (see left), allowed his

Paris drawings to appear in a "collaboration" with Irwin

Shaw, Paris! Paris!, produced lithographs of his drawings

(ah, Art!), created ads for American Express (ah, Commerce!),

published his cat books (ah, Sustenance), and created two of my

very favorites, The Illustrated Winespeak (at right) and

Slightly Foxed - But Still Desirable (ah, Satire!).

Searle continues to amuse and amaze to this day. His bite and his bark are equally ferocious, but always delivered with a wink (or is that a sly grimace?). His rise was meteoric and merited and the longevity of his reign is solely due to his talent. It's also our good fortune.

Thanks, Ronald, from a fan.

Mr. Searle died December 30, 2011.

To learn more about Ronald Searle, see:

To learn more about Ronald Searle, see:| Ronald Searle | Henning Bock/Pierre Dehaye, 1979 Mayflower |

| Ronald Searle, A biography | Russell Davies, 1990 Sinclaire-Stevenson |

| The Vadeboncoeur Collection of Knowledge | Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr. 1998 |

|

Illustrations are copyright by their

respective owners. This page written, designed & © 1998 by Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr. Updated 2011. |