| Coll's in #3 and on the cover of #5. and he's in #s 1, 2 & 5 of |

|

|

TWO great books on J.C. Coll from Flesk Publications. |

The Al Williamson Sketchbook was published recently

(well, "recently" back in 1998! -

today it would be the Al Williamson Archives, from Flesk Publications)

and

I was reminded of several things:

first was what a great artist Al was

second was the power of pen & ink as a medium

and thirdly, how much I loved the work of Joseph Clement Coll, one of Al's influences.

So, back in 1998, I went out on the web to see what I could find on Coll and discovered a page by Mark Wheatley (which is no longer there), a listing of a 1994 exhibit at the Brandywine Museum, some few mentions at Illustration House, and two hits from my own pages. One was just the listing of his name on my IllustratorS page and the other was my mention of him on my Harry Rountree page. This is obviously not enough exposure for the man who practically invented (along with Vierge) the modern heroic pen style. So this week I'm out to rectify that dearth. (I'm happy to report that in 2011, things have changed incredibly for the better.)

Back

in the late 1960s (yeah, so I'm old, big deal) I used to spend

time between college classes (well, okay, and instead of

classes, too) at a book store in San Jose, just grazing through

the shelves looking for neat pictures. I was on the trail of influences!

I knew Williamson's work from the Warren magazines, Creepy

and Eerie, and had read a few interviews with him that

listed the people he admired. I wanted to see some of them. If

that meant opening hundreds of books to see if they were illustrated,

okay. Anything was better than class...

Back

in the late 1960s (yeah, so I'm old, big deal) I used to spend

time between college classes (well, okay, and instead of

classes, too) at a book store in San Jose, just grazing through

the shelves looking for neat pictures. I was on the trail of influences!

I knew Williamson's work from the Warren magazines, Creepy

and Eerie, and had read a few interviews with him that

listed the people he admired. I wanted to see some of them. If

that meant opening hundreds of books to see if they were illustrated,

okay. Anything was better than class...

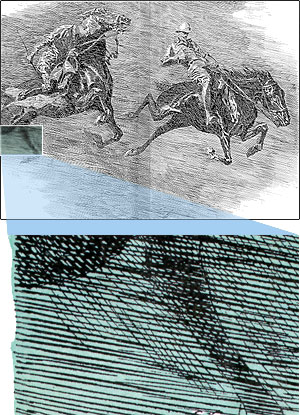

Back to 1968 and the bookstore and a copy of King of the Khyber Rifles that fell open to the double-page spread above left. I was stunned. Not only was it a gorgeous and powerful image, but (and here's where the web makes it hard to show you) the pen lines that formed the "fog" of the background were drawn right through the shapes of the horses! He'd drawn the background and built the structure of the horses on top of it!

Look at the enlargement of the leg of the rear horse. It's mind-boggling. The vision necessary to construct just that portion of the image floors me, but the entire drawing was like that! Fluid ink lines created textures and tones in the background without the slightest hint of being forced or planned and then he went back over them to draw the actual image and that looks even less forced. Suffice it to say, I was immediately as big a fan as Al and I searched through all the Talbot Mundy books I could find looking for more of his art. Found a good bit, too.

By

the way, the green tint in the enlarged part of the drawing is

from the original appearance of the illustration in Everybody's

Magazine for July 1916. It was serialized there with tons

more art than the six or eight plates that appeared in its book

form. Donald Grant released an edition of King of the Khyber

Rifles that reprinted all the illustrations from the serialized

version. It's a must-have book.

By

the way, the green tint in the enlarged part of the drawing is

from the original appearance of the illustration in Everybody's

Magazine for July 1916. It was serialized there with tons

more art than the six or eight plates that appeared in its book

form. Donald Grant released an edition of King of the Khyber

Rifles that reprinted all the illustrations from the serialized

version. It's a must-have book.

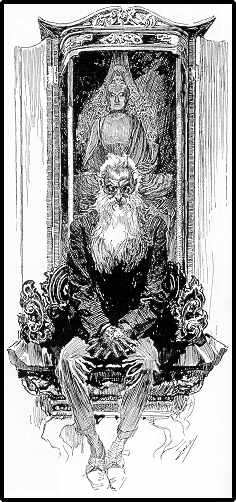

Joseph Clement Coll was born in 1881, the son of an Irish bookbinder. Self-taught from the works of Vierge, Pyle and Abbey, his talent was such that he was taken on as an apprentice newspaper artist on the New York American at the age of 17. He quickly learned the skills of a reporter and was sent to Chicago for more training. He returned to New York in 1901 where he worked on the newly-formed Sunday North American. The editor of the paper saw his talent and rewarded it with challenging assignments to which he often contributed in the lettering and design. The image at right is from his first assignment for the North American. I include it here to show just how accomplished he was at 20, and in honor of Richard Katz, a friend and fellow art lover who happens to own the original and bears more than a passing resemblance to the character depicted.

1902

saw the publication of Isn't It So?, a collection of bon

mots and sayings. The work is small and derivative (see at left),

but the pen line is alive. It's hard to remember that the ability

to reproduce pen drawings without engravings was a relatively

modern advancement back then. Until the 1880's, most art reproduced

in line was drawn in pencil, on wood, and printed from the engraved

wood block. Photography was initially used simply to transfer

the image to the wood and it took the insight and involvement

of Daniel Vierge to adapt

the process to the reproduction of his un-engraved drawing. It

was this revolution, scarcely a dozen years prior, that influenced

Coll so dramatically. We take it for granted now that the brush

or pen and ink are artistic tools, but Coll was breaking relatively

new ground and helping to define a medium.

1902

saw the publication of Isn't It So?, a collection of bon

mots and sayings. The work is small and derivative (see at left),

but the pen line is alive. It's hard to remember that the ability

to reproduce pen drawings without engravings was a relatively

modern advancement back then. Until the 1880's, most art reproduced

in line was drawn in pencil, on wood, and printed from the engraved

wood block. Photography was initially used simply to transfer

the image to the wood and it took the insight and involvement

of Daniel Vierge to adapt

the process to the reproduction of his un-engraved drawing. It

was this revolution, scarcely a dozen years prior, that influenced

Coll so dramatically. We take it for granted now that the brush

or pen and ink are artistic tools, but Coll was breaking relatively

new ground and helping to define a medium.

|

Coll's innovations were dramatic and popular. It wasn't long before he was drawing for Colliers, Everybody's and the Associated Sunday Magazine, among others. He was illustrating fantastic stories by the most popular authors of the day: Arthur Conan Doyle's Sir Nigel and The Lost World (also collected into book form in 1912), Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu (Colliers circa 1913 - a sample is at left), many stories by Talbot Mundy, The Messiah of the Cylinder by Victor Rousseau (post apocalyptic science fiction in 1917 - below), tales of Africa by Edgar Wallace, even a collection of stories from Dickens in 1910 (below left). Everything that was thrilling was fair game for his imagination and his skills just kept developing. Other artists were exploring the possibilities of pen and brush, but Coll was setting the standards. |

|

|

| He was a prolific artist, but the majority of his work appeared in the ephemeral world of magazines. Even the smattering of books that can be found are merely excerpted from the larger body of drawings that appeared in the serialized versions. | |

Fortunately,

there is another source. In 1978, Donald Grant published The

Magic Pen of Joseph Clement Coll by Walt Reed. It's a marvelous

book. The original edition was available in a hardback edition

limited to 750 copies and signed by the author, as well as a trade

paperback. We think both of these superior to the green-covered

softbound reprint, but that's just our opinion.

Fortunately,

there is another source. In 1978, Donald Grant published The

Magic Pen of Joseph Clement Coll by Walt Reed. It's a marvelous

book. The original edition was available in a hardback edition

limited to 750 copies and signed by the author, as well as a trade

paperback. We think both of these superior to the green-covered

softbound reprint, but that's just our opinion.

Coll died at the age of 41 from appendicitis in 1921. He had, in 20 short years, defined the look of adventure illustration. The pulp magazines would be full of his admirers. Fu Manchu and the other Eastern menaces were drawn from his design. J.R. Flanagan and the others who succeeded him sported their debt and their admiration proudly. When the pulps gave way to the comics, the next generation of fanatics discovered and learned from his pioneering work. Al Williamson, Roy Krenkel, Frank Frazetta, and hundreds more have felt the touch and "rightness" of his magic.

"Rightness" is the proper word. There were science fiction stories before The Lost World and The Messiah of the Cylinder, just as there were authors before Mundy and Rohmer who wrote horror and adventure stories. What there wasn't, before Coll, was the illustrative style and technique to match the literary ones. Coll invented that style, developed it, popularized it, and disseminated it to the coming generations of artists who saw it and knew that it was right.

Check out some of his work on paper and you'll see that I'm right. While you're at it, try to get that Al Williamson Sketchbook I mentioned at the beginning, if you can find it. And do not miss the two (soon to be three) volumes of Flesk Publications' Al Williamson Archives.

To learn more about Joseph Clement Coll, see:

To learn more about Joseph Clement Coll, see:

| The Magic Pen of Joseph Clement Coll | Walt Reed, 1978 Donald M. Grant |

| The Illustrator in America 1880 to 1980 | Walt and Roger Reed, 1984 Madison Square Press |

| The Vadeboncoeur Collection of Knowledge | Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr. 1998 |

| The Vadeboncoeur Collection of ImageS 3, 5, B&W 1, 2, 5 | Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr. 2002-2004, 2010, JVJ Publishing |

|

Illustrations are copyright by their

respective owners. This page written, designed & © 1998 by Jim Vadeboncoeur, Jr. Updated 2011, |